SALTWATER POSTMORTEM

Hi all! Today marks the 6 month anniversary of the release of my first game, SALTWATER, and I wanted to write up some thoughts about making and releasing it. I also just released a new trailer for SALTWATER, which you can view if you're interested.

I'm hoping this article will be useful to any artists/writers/programmers interested in working with interactive fiction (or really any storytelling medium) and also interesting to anyone else who read and enjoyed SALTWATER. I will inevitably spend some time recapping the full plot of SALTWATER, so if you haven't played it yet, I'd highly recommend going to do that right now (I'll put a second reminder a little later in the article before getting into larger spoilers for anyone who needs some convincing before playing.)

The Opening

SALTWATER opens on a conversation between two entities, neither of which are named. For the sake of discussion, here I will call them A and B: A's text is a bright white while B's text is a dull grey. To advance the scene, readers click on B's dialogue. A has been working on something grand, at a scale that B can't quite conceive of. A makes the following remark: "I am not much more than an observer, really. Nothing that I can do now but watch." The end of this scene starts Act 1.

Act 1

The first act of SALTWATER centers around 3 stories. In the files for the games I refer to these three stories as the following: "A Story of Water," "A Story of Love," and "A Story of Pigs." In all of the art assets for the game I shorten these names to simply "Water," "Love," and "Pigs." Here, "Water" refers to the story about August, her grandmother, the bartender, and Molly. "Love" refers to Rye and Mylo's story. "Pigs" refers to Alex and Liam's story. For simplicity, I will use these short-hands throughout the rest of the article, even though these names never come up in the text of the game.

Act 1 opens on a scene from Water: August wakes up from a dream about a desert to her grandmother insisting that the storm outside signals the end of the world. As her grandmother says: "'The rain, it's not water, look at it... It's blood.'" August does not believe her, but soon she starts coughing, and before either of them realize what's happening, she is dead. At the start of this scene, readers clicked on August's dialogue and actions that August took to progress the story. After August dies, readers click on "..." to continue the scene. The scene concludes with the reader clicking on the line: "The engine rumbled." This line is both the end of this scene—

And the start of the next. Rye is returning home following a call from their younger sister, Katy, pleading with Rye to come back home for their parents' funeral. Katy is suspicious that their aunt may be using the funeral as the way to force Katy into debt: she doesn't know what to do. This scene concludes with Rye trying to sleep on a lumpy motel mattress: "It was too hot to sleep." This line is the end of Rye's scene—

And the start of the next. Seven boys sit around a bonfire in an abandoned pig processing facility. Alex, the oldest boy at 17, keeps watch over the others. They are waiting for the pigs to speak, for the pigs to tell them what their final task will be. This scene ends with two options: "They heard a voice" and "They weren't really afraid." Both choices conclude the introduction to Pigs story and bring the reader to a different scene in either the Water or Love stories, depending on their choice.

These first three scenes serve a few purposes. Each scene introduces some important characters to each story and a central conflict that persists throughout all of the scenes in a given story. Further, the transitions between each scene establish the structure of the first act of SALTWATER as nonlinear. One of the main gimmicks of the game comes up here, it's never clear when the scene will change, and what scene will follow, but both scenes will always share at least one line.

A lot of the visual novels that I'm familiar with utilize a branching route structure, where a story follows a largely linear path until a choice (or set of choices) sets the player down a specific route or storyline, usually with its own associated endings. SALTWATER subverts this structure in a few ways. First, the player's choices never affect the content of the story. These choices do, however, affect what parts of the story are revealed to different players. Second, it's not always clear when one of the selections in SALTWATER will continue a specific scene or swap to a different one due to the structure of every ending to a scene being the start of another. This format was in part inspired by Stephen King's IT, which frequently switches between different perspectives mid sentence. Looking at other games that have done something similar, consider Half Mermaid's Immortality, which allows a player to select a specific object at any point in a scene, switching to another scene with shares that same (or, at least, similar) object.

In Immortality, forward progression throughout the story is never guaranteed. In this sense, SALTWATER is closer to a more traditional visual novel. If you plotted the scenes that can be seen in Act 1, you'd get something that looks like a tree structure, albeit here every branch intersects with the linear progression of events in a given storyline in odd ways. Seen this way, there are roughly 3 different ways a player can progress through Act 1 of SALTWATER. Each route gives players a few snippets into each story. This produces a sometimes obscure progression of events: characters and conflicts appear and disappear as players return to the three main stories of SALTWATER.

A few sources of commonality help tie everything together. Each story takes place in the same town, during the same night, and under the same storm, and by the end of each story, everyone has gone to the town's church.

The End of Act 1

The conclusion to Act 1 was the most difficult scene to write in SALTWATER, both practically and on an emotional level. Looking at the former, the end of Act 1 pushes the format of the story so far to an extreme. Instead of the perspective switching between different scenes, the perspective now switches only every few paragraphs and the previous text does not get cleared. The number of characters in this scene is fantastically high when compared to previous scenes. As the different groups interact with each other, I was careful to keep in mind how these characters were unfamiliar with one another, keeping each perspective highly limited. Despite this, the specific events of this section are fairly straightforward: Molly and the bartender take August's body to the graveyard and get intercepted by Alex and the other boys, who want to burn the graveyard to the ground. Rye and Mylo find themselves getting involved after August's grandmother pleads with them for help. As the storm escalates, the group tries to get into the church, but the doors have been bound together in chains and they aren't able to get in. The narrative complexity in these moment deals with very low-level details, like who can hear who at any specific moment in time. Sometimes a character will hear a scream in the distance. If the reader chose a different option, they'd see why someone screamed.

Emotionally, this ending lacked a sense of finality. The events are grim, every character present dies from drowning, but there are things about the church that do not add up. Why had the handles been bound together? What could the characters see shining inside the church through the stained glass windows?

Note: If you haven't played SALTWATER, but have found anything I've discussed so far to be interesting, I would highly recommend playing SALTWATER and then coming back to this article.

An Intermission

Before Act 2, readers find themselves in a place similar to the opening that precedes Act 1. The two narrators, A and B, are back again. A's dialogue indicates that a lot of time has passed, and since then A has deteriorated mentally. Their creation is not producing the expected result. It's fake, melodramatic. And yet A, who now suffers from nightmares due to what they have done to their creation, persists. Act 2 starts.

Act 2

Act 2 opens in a familiar scene with an unexpected background. August is dying in the same way she died at the end of Act 1. This is a dream. She explains that she has lied about her dreams in the past not to worry her grandmother, conjuring up fake images of the desert seen in the beginning of Act 1. The middle of this scene plays out roughly the same as the Act 1 equivalent, but something is off. Instead of dying, August remains barely alive.

While the structure of Act 2 is identical to Act 1, the context of many scenes have been flipped to tell a different story. In the Water route, August comes to realize the position she's in and makes her way to the church before anyone else gets a chance. The totaled car seen later in this route still catches fire with someone inside, but now it's Molly inside of the car, not August. In the Love route, Mylo's presence in the later scenes becomes ghostly and unreal. Rye remembers Mylo, but he doesn't seem to really be there. Rye's memories aren't adding up with reality. In the Pigs route, the perspective zooms in on Alex and readers see a different angle on the cult of pigs: who are these kids? How did they get here? Readers also see more of a girl, Amy, who had previously followed the pigs around in Act 1.

Along with these broad changes, Act 2 introduces more moments into the narrative where reality starts to fray at the seams. For a dazed moment, Rye notices the pigs standing outside a window and pursues them down to the church, where the ending to Act 1 is already playing out. In the Pigs route, on Alex and Liam's first foray to the factory, Liam encounters someone else in a pig mask who gives him a crowbar, telling him not to let go. In the Water route, the radio declares that they are all going to die again, and again, and again.

When reading through traditional visual novels and other works of interactive fiction, there's sometimes a sense that you really need to be reading a work multiple times over to get the full story. Act 2 of SALTWATER was directly inspired by this dynamic: What does it mean to come back to a familiar story a second time with more context? Act 2's answer to this question is that stories change between repitions. Here, the change in the narrative bring the reader closer to the characters. Act 2 is, in many ways, more honest than Act 1. But it's not quite there yet.

The End of Act 2

By the end of Act 2, things have turned out differently. Now standing in front of the church doors, instead of a whole cast of characters, there are three: Rye, Alex, and August's grandmother. After seeing the events at the end of Act 1, Rye made sure to bring an axe to cut the the chains off the door, but they're already gone by the time they get there. The three enter the church.

The format of the first half of this scene is similar to the end of Act 1, but with some tweaks. Instead of choosing from two perspectives to advance the story, readers have choices between all three of them. Similarly to the end of Act 1, these choices don't influence the material of the story, but rather what the player actually sees and interacts with while this is all happening.

Each of the characters in this scene is looking for someone: Rye wants to find Mylo, Alex wants to find Liam, and August's grandmother wants to find August. The characters fumble around with the lights, searching for their loved ones, until they all hear a voice from the front of the church, readers here choose someone's route to follow through the end of the scene. These routes start similarly: the lights turn on revealing a grotesque scene of bodies strewn around the church, hanging from the ceiling, etc. The characters close their eyes, trying to unsee the scene, before opening them again to a bright church, the opposite what they all saw a moment ago.

The end of Act 2 plays out differently for each character, but similar things happen in each. Alex wakes up at a ceremony where the other boys, including Liam, are graduating. August's grandmother wakes up at August's wedding day. Rye wakes up at their own funeral. In each of these cases, something is wrong. At August's wedding, August keeps tripping and falling at the same part of the aisle as she walks up its length. She stays for far too long before getting up. The faces of the other people at the wedding look blank and unreal. At the graduation ceremony, Alex tries to talk to Liam, but he can't hear a word he says. At Rye's funeral, Rye can't seem to communicate with Katy. When Alex tries to touch Liam, his shoulder falls away like sand. August's grandmother sees the same thing happen when she reaches out to one of the blank strangers around her.

Rye, Alex, and August's grandmother are only able to find their way out due to the help of another character. Katy approaches Rye in a waiting room and hands them back the axe they left outside the church. August talks to her grandmother during her wedding vows and her grandmother realizes there's something past the floor where August keeps tripping. Amy tells Alex about another place that she had just come from. Each of the characters return to the grisly scene from earlier, but now the building had caught fire. The light from the end of Act 1 had grown into a great conflagration. In each route, despite the reader clicking on a command: "Go back," the characters stand their ground in the burning building.

I wrote the end of Act 2 to feel similarly inconclusive to the end of Act 1. Whereas the end of Act 1 felt simple and bleak, the end of Act 2 rings more hopeful, but the situation of the characters has grown substantially worse. None of the main characters are happy to exist in limbo as their fight for their loved ones brings them back to a crushing reality, but this conflict has grown larger than that of a simple storm. These characters are not in control, however much they wish to be.

A Second Intermission

This is the shortest intermission, and arguably the simplest to understand as well. Narrator A apologies to B for doing something bad. A is giving up. A wants to spend what time they still have loving the world. A and B gather once more to listen to the third act.

I don't want to take away what anyone thought of these scenes or how they interpreted them, I wrote them to be intentionally vague and fuzzy on the specifics, but I hope I was able to get across that the events of the main story are a result of an increasingly emotionally turbulent narrator A. In Act 2, for example, the characters grow more aware of what they are. This mirrors narrator A's growing worries that their own story is escaping them, taking a life of its own. Now narrator A feels guilty for what they have put the characters through and passes the baton to the characters to tell their own story.

Act 3

Act 3 is told entirely from a first person point of view, with the pov character frequently switching between different scenes. The mode of interaction has changed, too. Instead of selecting a specific line of dialogue, readers click on an ellipses to progress from one moment to the next. There are no choices in this act. It will play out the same, regardless of a player's intentions.

The story starts again in a familiar scene: everyone is drowning again. August is looking for her grandmother in the carnage.

The scene shifts to Rye's portion of Act 3. For every storyline in the first 2 acts, there is a large scene in Act 3 composed of two intertweining narratives. The first of Rye's narratives takes place in the winter at a cabin. They are dealing with the loss of Mylo. Rye's other narrative seems them meeting Mylo for the first time. The scene flips back and forth between these stories to reveal that Mylo wasn't a real person, but that Rye still feels grief for cutting that part of themselves off.

August is now back in the desert. The same lines from the start of Act 1 are told again from the first person point of view.

Alex's portion of Act 3 splits its time between recounting the names and personalities of each of the boys while telling the story of how they had stumbled onto a body in the forest. It is this moment that lifts veil too far for the boys, causing them to retreat into the factory walls seen in the previous acts. I was initially worried about my choice to introduce each of the boys separately this late in the game. At this point, why bother introducing each of these characters when they will only have a scene or two left? To me, a lot of the Pigs route was about identity, in a sort of round-a-bout way. The conclusion to this story had to give something more to these kids, to give them names and personalities, to show that it matters even if it won't last. I didn't do this with every named character in the story. For some characters, such as the bartender, it felt better to leave them with some space by the end of the story. It would have been too soon for some of these characters and I didn't want to be intrusive.

The last segment of Act 3 proper goes back and forth between Molly and the bartender as they recall anecdotes and stories, many about their upbringing. These characters are one of my favorite pairs in the full story due to the way they contrast each other. Molly wants to leave everything behind and to always stay in motion while the bartender finds himself incapable of doing so, no matter how much he may want to.

The End

The end of SALTWATER brings most of the characters back to the church. Many of them, aside from August, seem confused. They can't remember how they got here. The perspective of this ending following the following pattern: August's perspective comes first, then Amy's, then Katy's. These are the same characters that helped August's grandmother, Alex, and Rye during the end of Act 2. Those three characters, however, are noticeably missing, along with the rest of the pigs.

Molly is so close to getting it, she's the closest character besides August at this point at understand what's going on. Katy and August fight: August wants to protect everyone from what she knows is inside the church, while Katy needs to find Rye. Katy wins out, opening the doors to a completely empty church. They sit together inside, waiting out the storm, when the floor pushes the boys into the church. They're cold and wet. The group huddles together.

This moment was important to me as its one of the only moments in the story where characters from different storylines crossed paths and helped each other. At one moment, Gregory, one of the boys who had been named earlier in Act 3, tells the other characters that he loves them, even if this is the first time they're meeting.

The rain outside turns to snow. Katy leaves the church, and outside they find August's grandmother, Rye, and Alex laying together in a pile of snow. The group manages to get everyone inside, where they try to keep warm as best they can. Everyone is still alive, despite the circumstances.

The end of SALTWATER takes place over the course of three different dreams that happen after the characters fall asleep that night in the church. August dreams about driving around the country with her grandmother. Amy dreams about herself, her sister, and the boys eating dinner together. Katy dreams about spending Christmas with Rye. Everyone dreams about love in the many forms it can take.

August is the first to wake up. She looks at the moving silhouette of a tree in the sunlight. SALTWATER ends on this line: "It's time to go."

To me, the ending of SALTWATER was about two main things. Firstly, it was about love, and by extension the way people come together. In contrast to the previous two endings, the ending of Act 3 sees the characters primarily stuck with each other without a sense of external pressure beyond the storm. There's nothing for them in the church to fear or fight against except for one another. While they start by bickering in a similar way as was seen in the endings of Acts 1 and 2, they learn to be there for each other. The end of SALTWATER is also about moving on. When August wakes up and leaves the church, the sun is shining through a tree, but it won't shine that same way for the whole day. And the next day, even if the sun rises in a similar path, it won't ever be quite the same again.

Notes On Writing and Narrative Design

I'd like to talk a bit about how I put together the story for SALTWATER together due to its lack of straightforwardness. The narrative scripting language used for SALTWATER was ink, which allowed me to separate my writing into different files (I used one for the openings/intermissions, one for each storyline, one for Act 3, and one for each of the endings.) The final game ran using Calico, an interactive fiction engine for web games.

I won't go into the specifics of syntax in Ink (you can view their documentation here), but I'd like to talk about how I structured these scripts for anyone familiar with the language. Every scene in SALTWATER was created as a knot. The same knot was used for scenes that appear across Acts 1 and 2. I tracked the internal logic of what Act the player was on using an Ink variable. Sometimes, when scenes would significantly diverge across different acts, I used a stitch within the knot (think of this as a knot within a knot.) Below is the code used for a scene in the Pigs storyline, with some parts redacted (indicated with "..."):

=== Pigs_0 ===

#clear

#background: pigs_0

#play: cicadas.ogg

- "I shouldn't be here."

...

+ [I don't like this place.]"I don't like this place, Alex."

- "Dad used to work here, you know. He and some other people made things, food stuff. Nothing scary."

+ {Act == 1}[Nod.]Liam nodded.

-- Alex put Liam at ease, even if he didn't understand why his brother wanted to be out here.

...

+ {Act == 2}[It's scary.]Liam shook his head.

-- Seeing through broken windows...

...

-

...

+ {Act == 1}[What is it.]"What is it?"

-> Pigs_0_1

+ {Act == 2}[What is it?]"What is it?"

-> Pigs_0_2

= Pigs_0_1

- "Can you hear anything?"

- Liam listened...

- Beneath the groan, Liam could hear something beating.

+ [Yes.]"Yes. It's like, I don't know. I'm scared, Alex."

+ [No.]"No. I don't know. I'm scared, Alex."

...

+ [I want to run away.]

-> Love_4

+ [That's not a person.]

-> Water_2

= Pigs_0_2

- "Can you see anything?"

+ [Look.]Liam looked between the factory doors...

- It stepped out from the doors...

...

+ [I want to run away.]

-> Love_4

+ [That's not a person.]

-> Water_2

Everything for SALTWATER was written inside Inky, a custom editor for Ink with some handy debugging features. This had its pros and cons. I liked being able to write the scenes with the logic of the game in mind. Writing Act 2 would have been much harder if I had to write the content first, and then adapt it to fit my (admittedly weird) scripting format. On the other hand, the version of Inky I used did not have a spelling/grammar checker. This meant that I had to spend a lot of time after revising the finished script on editing. Even after enlisting some friends for help in spotting typos (if you're reading this, thank you), I still made well over a dozen fixes in the week after launch. There's probably still more in there that I haven't caught, oh well.

Here is a collection of stats from the Inky project for the curious (note that this may take into account some unused content:)

Words: 37448

Knots: 31

Stitches: 40

Choices: 715

Gathers: 1004

Diverts: 113

I'm hesitant to open source the script used for SALTWATER as a lot of it is quite messy and some sections use a lot of tricks which I don't suppose are very good practice. Feel free to message me though if you have any questions as to how I did a specific thing as I'd love to help anyone else working on similar projects!

All of the stories in each act of SALTWATER were written roughly in parallel. I had an idea of what I wanted to happen in each route, but I did not plan ahead the specific moments of transition and branches between the different routes. Generally, my goal would be to write out a scene such that it provides some amount of context on a specific storyline, while still having an independently interesting conflict that could function on its own. After a scene started to get too long, meaning the focus of the scene would shift, I would start looking for ways to tie the end of one scene into the start of another. With three different storylines set in a similar place dealing with similar themes, this was never particularly hard. What was difficult, however, was working to revise certain scenes. If I wanted to cut a given scene, for example, I would have to find a way to stitch two other scenes together. This was awkward, but largely unavoidable without compromising on any of the things that I think make SALTWATER interesting.

While writing, I made an (admittedly silly) choice to not speak about the content of the game to anyone until it was entirely finished (aside from some minor revisions and editing work.) While I enjoyed seeing the reactions of my friends after they played it for the first time, spending a year not being able to talk about SALTWATER was just awful. I would not recommend this, if you can avoid it at all.

Notes on Genre and Horror

On Itch, I labelled SALTWATER as a "horror" game, a decision I'm still in two minds over. On one hand, I did not want anyone to play SALTWATER and to feel surprised by the content of the game. There are broad sections of the script that I wrote specifically to instill some amount of fear, similarly to other horror works. On the other hand, after spending enough time writing and illustrating SALTWATER, I think sometimes the connections seem a little bit light. Being written over the course of over a year, I naturally had over a year's worth of influences impacting the narrative and artistic choices I made, and many of these influences existed outside of horror. Many writers much smarter than me have written much smarter thoughts than what I could come up with about about what exactly it means for something to be horror, or to not be horror, so I will not do that here, don't worry. I do hope though that anyone who comes across SALTWATER could keep a relatively open mind and enjoy the story for what it is.

Notes On Art

There are a little under 50 background illustrations used throughout SALTWATER. These illustrations serve both a practical and aesthetic purpose. Speaking practically, I used different illustrations to differentiate between different scenes. When a player encounters a specific illustration, they know roughly where they are in the story. This is particularly important in a few spots of the narrative. During the ends of all three acts, the art of the church changes to indicate which storyline is being followed. This is important as these scenes are written to fluidly move between different perspectives, and having some kind of visual indicator of what's going on makes things easier on readers as they can associate each story with an illustration as opposed to searching for character names to contextualize a paragraph. The earlier parts of Act 3 are similar: using two different illustrations makes it easier for readers to navigate a scene that takes place in two different perspectives. Throughout the earlier half of Act 2, a familiar illustration may indicate that a player has seen a scene before in Act 1. This makes following the similarities and differences between both Acts a little more intuitive as its easier to remember illustrations as opposed to specific lines that repeat in both acts.

In addition to some of these more practical uses, I wanted to have a few moments with some more involved visual flare. The most obvious example of this is seen with the end of Act 2, which uses black text on a lightly colored background to indicate that the player is in a very different place from where they were before. Throughout the rest of the game, I wanted the illustrations to give off a feeling of darkness and dreaminess.

The consequence of SALTWATER requiring a great deal of illustrations was that I had to somehow make a great deal of illustrations in a short enough time period that I could get the game out by Halloween of 2023. I used a variety of tricks to ease this burden of doing so many illustrations without sacrificing on visual quality or style. I made all of the illustrations in Photoshop, but these techniques should work in most modern digital art programs. Let me walk through how I made this piece, which can be seen during the Water storyline:

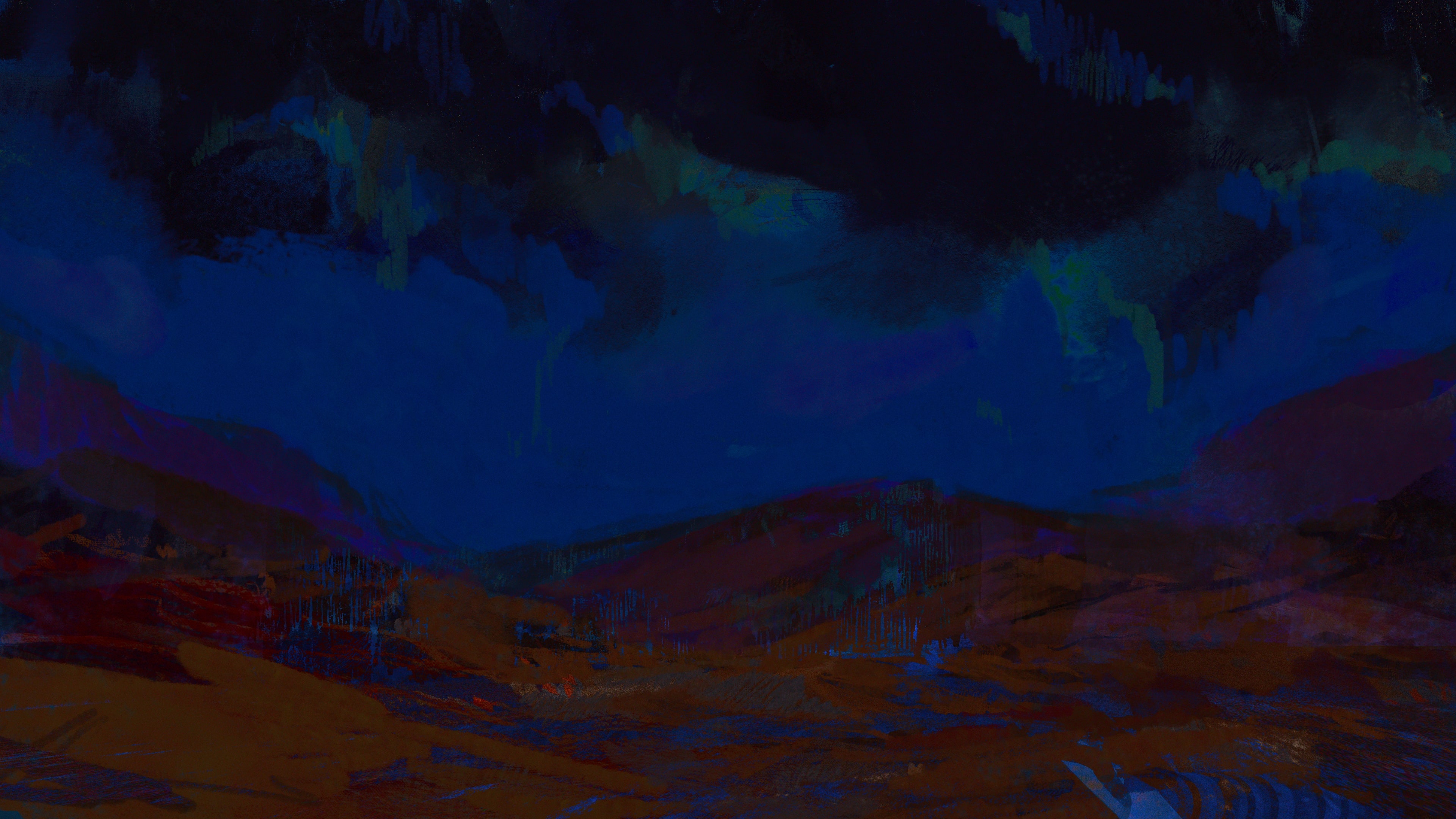

First, I started by copy-pasting a previous illustration I had done for SALTWATER into the Photoshop file:

I usually started a new painting by using an old painting as a base. This way, I already had some values, colors, and textures on the page. For this piece, I used a curves adjustment to change the color palette slightly, while still preserving a lot of texture that I didn't want to recreate by hand again:

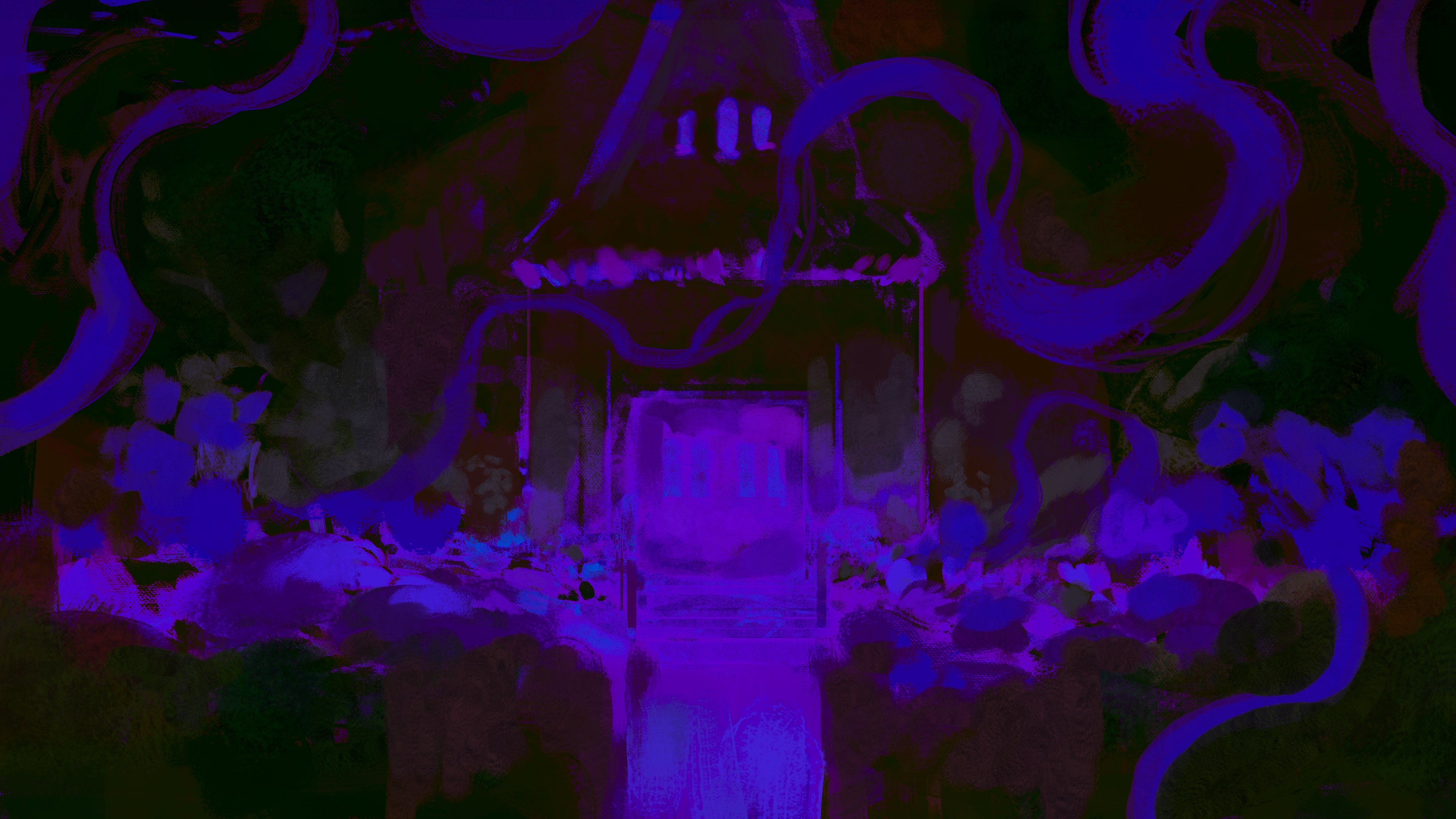

Now it looks a lot darker and more green. I wanted this illustration to show a bright blue light coming from within a car window, so I began painting over what I already had:

The smoke was looking a little too crunchy for my taste, so I softened it up:

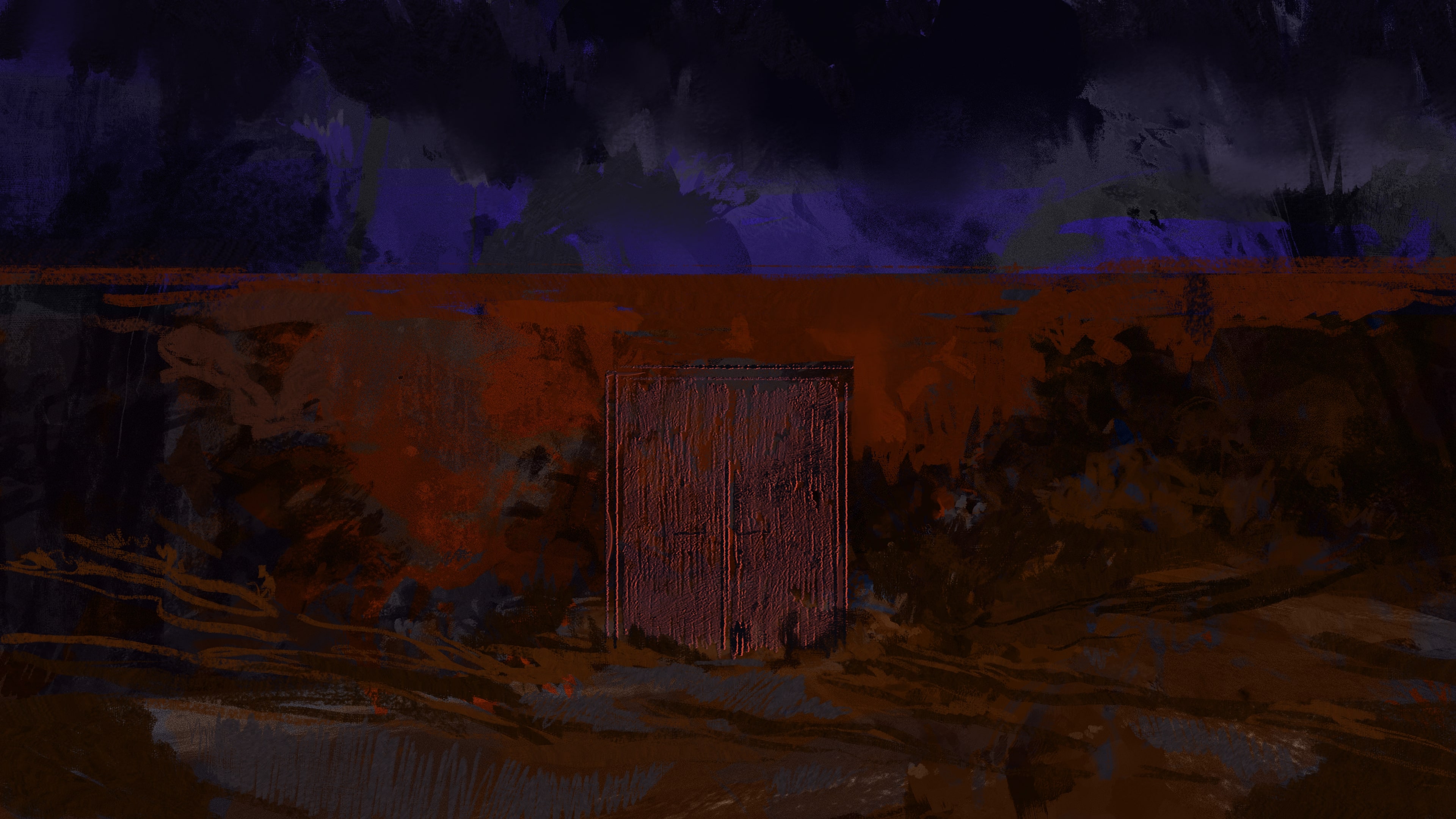

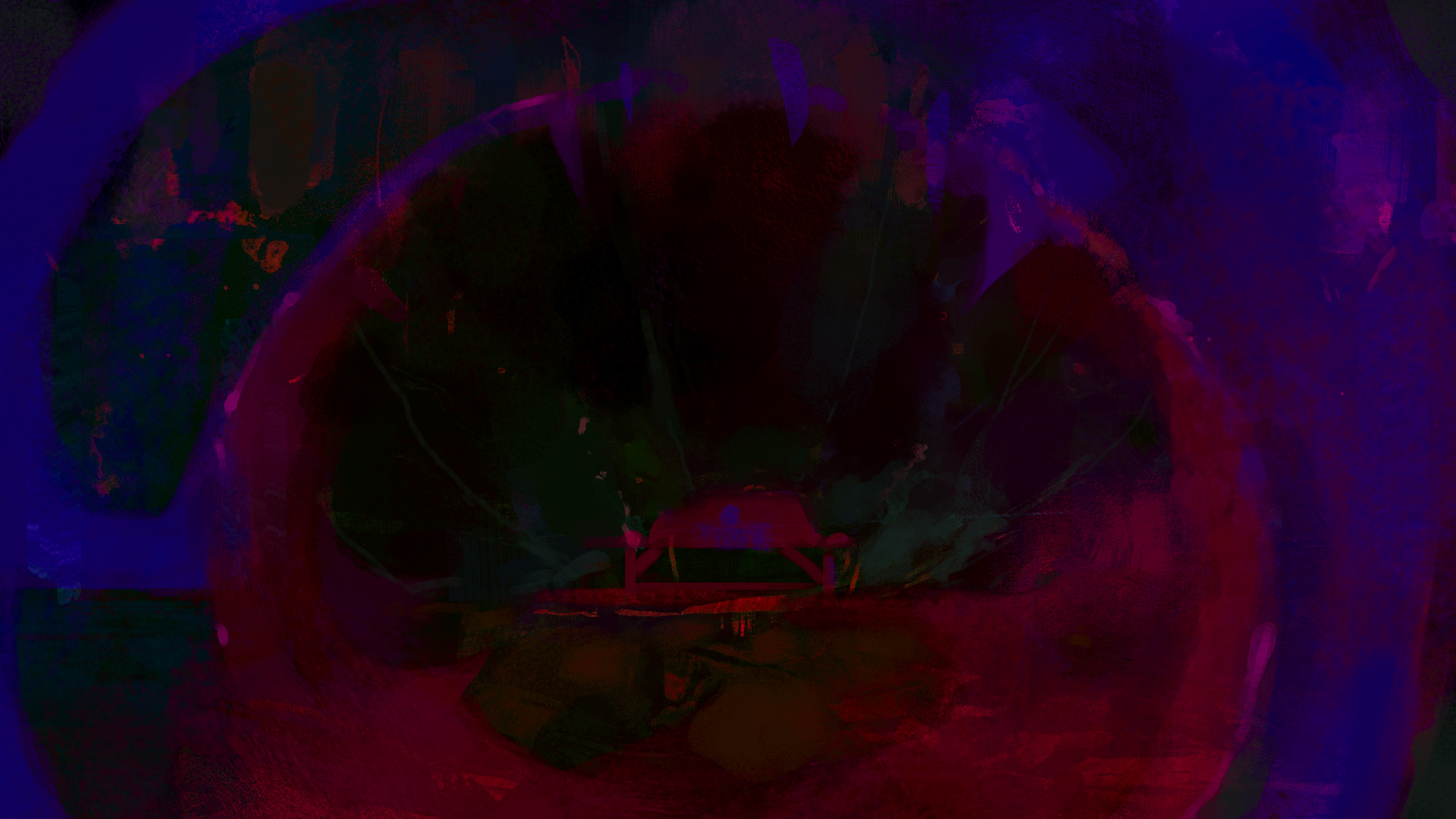

Finally, I went through with a very chalk-y brush to finish things off:

By using some of the work that I had already made, I was able to lower the amount of time I needed to spend getting a color palette that was just right or slowly building up textures from scratch. Thus, I think most of SALTWATER's illustrations were done in about an hour, and sometimes in even less time.

There are some consequences to this technique, the obvious one being that anyone with a keen eye can spot that I had reused some parts of some painting (look at the tree on the left in the example above!) In the case of SALTWATER, I don't think this is actually a bad thing, as similarities between different pieces can produce a feeling of dreaminess as things start to blend together. Additionally, I tried to minimize how much I'd cross contaminate pieces, meaning that illustrations in the Water storyline would usually be built off of other illustrations in the Water storyline. The consequence of this is that nobody would ever see two illustrations from the same storyline back to back, so it wasn't a huge deal.

If anyone else is interested in applying a similar technique, instead of starting with a previous painting, I'd recommend overlaying a previous painting on top of a painted sketch instead. Functionally, this is similar to overlaying a noise or paper texture onto a drawing with the added benefit that you can get a wider variety of effects. Traditional artists can also use this technique: try taking an old painting, maybe one that you didn't like, and try creating something new on top of it. You might get something you find interesting!

Note that at the time of making SALTWATER, my computer was rarely able to run Photoshop at a speed that I thought was good enough to paint with on large canvases. I changed my color profile from RGB Color to Lab Color and that significantly sped things up. The way colors mix will look different (in some cases I think they looked better), and you don't get the same access to all of the layer adjustment options, but if you have any performance problems I'd recommend trying it out.

Notes on Length

SALTWATER was always intended to be a pretty long game. According to the Inky stats for the script, there are over 35k words in SALTWATER. This is likely under-counting the amount of text someone would have to read in order to see everything in SALTWATER, however, since many lines are shared in the script between Acts 1 and 2. In between the word count and the amount of illustrations, this was a big solo project for a debut game. I'm still worried that the length, absent of any proper save feature, will turn some people off from SALTWATER. At the same time, I don't think I could have made SALTWATER any shorter without sacrificing on the parts of it that are interesting. I couldn't have written it any differently.

Notes on Release

SALTWATER released a few months later than I had initially planned, but the release date ultimately coincided with Halloween, which was a fun coincidence.

Despite SALTWATER having a total budget of $0 and me being quite bad at marketing (who else releases a trailer for a game 6 months after the game comes out?), I have been continuously floored seeing people review SALTWATER, add it to collections on itch, and so on. In the November following SALTWATER's release, I submitted it to be included in Indiepocalypse Issue #49, which was an incredible experience. I can't recommend other developers go check Indiepocalypse if they haven't already. The same also applies to readers who enjoy interactive fiction or smaller, more experimental games, and want to see more projects like SALTWATER out in the world. Despite me not having promoted SALTWATER much at all over the past few months, during the process of writing this blog a very kind stranger made pages for SALTWATER on VNDB and IFDB respectively. Sincerely: thank you!

Deleted Scenes

Finally, in the spirit of SALTWATER inevitably being in some ways about the writing process itself, I figured I'd share some deleted scenes that were tucked away as comments or hidden in a Google Doc, somewhere. None of these are "canon," but you might find them interesting.

The following passage was left in a multi-line comment at the end of the Pigs script file.

THE GROUND IS ALREADY CRACKING. I CAN SEE THE SKY AGAIN. I HAVE WAITED TOO LONG. THIS ENDS TONIGHT. I WILL DRINK THEIR BLOOD, I WILL EAT THEIR SKIN. I WILL TOSS THE REST AWAY. I WILL LET THEIR EYES AND HAIR AND ORGANS FLOAT DOWNSTREAM ON A RIVER OF SALTWATER. ETERNAL DAMNATION BE UPON THEM.

I HAVE GATHERED THE BODIES IN THE VESSEL OF THE CHURCH. NO EARTH IS STRONGER THAN I. THE WIND BLOWS BEHIND ME AS I BREATHE. I AM BLESSED.

IT IS STILL NOT ENOUGH. IT IS NEVER ENOUGH.

The following interlude was functionally replaced by the openings seen in the final game. I think this felt too grounded and obvious. It didn't work thematically with what I wanted to say. I preferred the final version of what happened in these openings.

=== Interlude_0

#clear

* ...

- That's the way I heard them tell it the first time. I don't think they were telling the truth.

* Who are you?

- I'm nobody important.

- A few weeks ago I got an email from a friend of a friend. He had been staying at home with an old relative for the past few weeks. He asked me if I could come and sit the house and stay with his relative for the week, said he'd pay me. I asked how much. It was enough to get me to call in for work and make the 4 hour drive down south to his house in North Carolina.

- When I got there, I didn't much understand why he wanted me. His relative-- he didn't tell me the relation-- was fairly quiet. They spent their time walking around the yard and sorting through some old antiques. Every night, they would turn on the radio and listen to a station that played songs I couldn't recognize. I would sit there with him. They would start telling me stories.

* What kinds of stories?

- Small ones, ones about going to the post office and talking to the workers there, they were all pretty recent. They would repeat stories between the days, sometimes say them a little differently, remember a detail they forgot the first time, maybe forget another one.

- Last night, they told a different story.

* What story?

- It started with a girl named August and her grandmother. August died and her grandmother had to find some way to deal with it. Then, without skipping a beat, the story was set somewhere else, about someone else entirely. They kept going like this, transitioning between stories until all of the characters were together and they all died in a flood. They started crying a little after the ending. I felt bad, like I should have stopped them earlier. I took them to bed right after.

* Was it real?

- I'm not sure. It didn't sound like they were making any of it up, all of their stories so far have been about real things, or atleast things I could imagine being real. I can't imagine coming up with all of that on the spot from nothing. I rung a friend later that night, asked her if she could look something up for me. I wanted to see if something like this really happened at one point, maybe they had adapted it all from an article they read in the paper. She couldn't find anything. There had been floods in the past few decades around here, some of them had several casualties, but nothing like that.

* Have you asked them about it?

- I haven't. We don't really talk much, that's fine. I'm nobody, really. I don't mind it. I do wonder about it though. Maybe he'll tell some part of it again tonight, they do always like telling stories a few time.

* What if they don't?

- I'd be fine with it. Especially if it means they'll have a nice evening. I got real concerned last night that they wouldn't be able to sleep. I don't know. We'll see.

* [We'll see.] -> Opening_2

-> DONE

I believe this next segment was written about Rye initially but now I think it fits better with August's story.

They ran faster than their legs could ever take them. They would keep running until there was no pavement left for them. When the pavement stopped, they'd run through fields until they reached the ocean. And then they would jump. They would jump so high they escaped the pull of gravity. And then they would continue. They would go so far, they would scream, they would tear the stars apart, and yet it wouldn't matter. It would end the same anyway.

There was never any real avoiding it, but maybe it'd feel good to try? You know, going past the limits expected of them. Trying to do the impossible.

Conclusion

I hope this article was of use or interest. If you'd like to read more things I've made, be sure to go check out GUARDIAN ANGEL and the postmortem I recently released for that game. Furthermore, keep your eyes peeled for my next project, REPEAT IT BACK TO ME, which is set to come out sometime this summer (hopefully.) If you'd like to see more of my illustration work, you can find me at any of the links here!

Thanks,

- Sky

Get SALTWATER

SALTWATER

Narrative game about the end of the world and a world that won't end.

| Status | Released |

| Author | SkyShard |

| Genre | Interactive Fiction, Visual Novel |

| Tags | Atmospheric, calico, Experimental, Horror, Narrative, Nonlinear, Psychological Horror, Story Rich, Text based |

| Languages | English |

More posts

- PWYW Wallpaper Pack Out Now!Jan 13, 2024

- Windows Build + Other FixesNov 17, 2023

- SALTWATER is out now!Oct 31, 2023

- September Update + Release Date AnnouncementSep 30, 2023

- August UpdateSep 01, 2023

- July UpdateJul 31, 2023

- June UpdateJun 30, 2023

- May UpdateMay 31, 2023

- April UpdateApr 30, 2023

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.